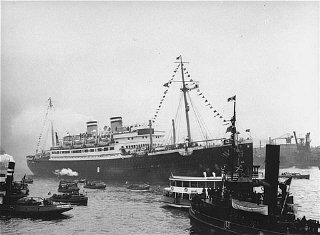

The S.S. St. Louis

During the first five years of Nazi rule, from 1933 to 1938, half of Germany’s 600,000 Jews remained in the country, because they believed that anti-Semitism would soon diminish. After Kristallnacht, they understood that they had to emigrate. Thus, tens of thousands flooded the foreign consulates throughout Germany for visas. The problem was that few countries were willing to accept them. Immigration quotas were widespread. Even Palestine was not an option. The British government, which controlled Palestine under the Mandate, had just issued a White Paper, shutting off any possibility that Jews could seek refuge in what was to become the Jewish homeland in less than a decade. The S.S. St. Louis was part of the Hamburg-American Line. It had been docked in Hamburg, waiting for its next voyage to transport German Jewish refugees to Cuba. They would remain in Cuba until they met the quota requirements to enter the United States. The cost of this trip was exorbitant; most Jews could not afford it. Almost all of them had lost their jobs. The Nazis had forced them to pay steep rents for their homes or apartments. Relatives from outside Germany, in some cases, had sent them money. Several families had to pool their resources so that just one member of the family could leave, thus rupturing family units. Each person was permitted to take the maximum equivalent of $4.00 in cash upon leaving. On May 13, 1939, six months after Kristallnacht, 937 men, women, and children, boarded the S.S. St. Louis for Cuba. 930 of them were Jewish refugees from Nazi persecution – among the last to escape from Germany’s tightening restrictions on emigration. One passenger was Aaron Pozner. He was among the 26,000 Jews sent to concentration camps. There they lived in unsanitary conditions, subsisted on meager rations, and engaged in forced labor. Pozner himself had been interned at Dachau, where he had witnessed inhumane scenes. Some Jews were put to death by hanging, drowning, and crucifixion. Others were tortured by flogging or castrated by bayonets. For some unknown reason, the Nazis released Pozner from Dachau on condition that he leave the country within 14 days. On his way to the S.S. St. Louis, he was beaten and forced to sleep among bloody animal hides. Coming from a family of limited means, he managed to gather enough money together to obtain a ticket for the ship. At Hamburg, he said good-bye to his wife and his two children, knowing that they themselves could never accumulate sufficient funds to gain access to freedom. He hoped that he could earn enough money after his arrival to bring them out of German captivity. Many other passengers on the S.S. St. Louis, upon their arrival, planned to join relatives who had left Germany earlier. On the gangplank, they feared the kind of treatment that they would receive on the ship. After all, a Nazi flag dominated the top of the ship and Hitler’s portrait covered the wall of the social hall. These blatant signs of Naziism did nothing to assuage their apprehensions. Since the S.S. St. Louis was a luxury liner, life aboard the ship was surprisingly quite pleasant. The ship offered the passengers an abundance of fine food, games, movies, and swimming pools. Many enjoyed reclining on their deck chairs, where they read good books. Children began to form friendships with each other, and even managed to play a few pranks. The ship’s captain, Gustav Schroeder, also had ordered his 231 crew members to treat the passengers humanely. The passengers were shielded, even from two tragic episodes aboard the ship. One passenger had died and had to be buried at sea. This burial was done at 11:00 at night so as not to disturb the other passengers. One-half hour later, one of the despondent crew members jumped overboard at the very site where the burial at sea had just taken place. After several hours of searching, his body was never recovered. The ship arrived near the Havana harbor two weeks later, on May 27, 1939. The passengers were unaware of a disappointing development. Cuba’s government had changed, just a week before the ship had sailed. The new government would not honor their visas. The new administration ruled that only 28 passengers held valid passports and could enter the country. Complicating the process was the Nazi propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels. He had decided to exploit the case of the S.S. St. Louis and its hapless passengers for his own nefarious purposes. Knowing that Jews would be coming into Cuba, Goebbels engineered an anti-Jewish hate campaign there. He spread the word that these Jewish immigrants were criminals and would be a threat to Cuba. In fact, five days before the S.S. St. Louis left Hamburg, 40,000 Cubans took part in a demonstration against Jewish immigration to Havana. The ship stayed in the Havana harbor in the blistering heat for one week, while officials of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee tried to gain the admission of the rest of the passengers. Friends and relatives waited on shore, and some even hired motorboats to sail out to meet the ship. Because the ship was stranded in the Havana harbor, the passengers on the S.S. St. Louis became increasingly suspicious and apprehensive. They knew that if they returned to Germany, they would eventually end up in concentration camps. One desperate passenger even slashed his wrists and jumped overboard. He was rescued, but he never reboarded the ship. No efforts seemed to persuade Cuban officials to change their ruling against the visas. Now that the ship could not dock in Cuba, Captain Schroeder sailed it to the Florida coast. There he hoped that the United States would admit the passengers. Desperately trying to avoid a forced return to Germany and certain death, the passengers – more than 400 of whom were women and children, and many of whom actually had quota numbers to eventually enter the United States – sent a telegram to Roosevelt asking for help. They received no reply. The State Department sent word that it would not interfere in Cuban affairs and refused to allow the passengers to come ashore. In fact, even as the ship was entering Florida’s territories, the Coast Guard had fired a warning shot in its direction. The captain knew that there was no choice but to turn back toward Germany. Sailing along the coast of Florida on its way to Europe, the St. Louis was shadowed by a Coast Guard ship to prevent passengers from swimming to freedom in the United States. The New York Times lamented, “Off our shores she [the St. Louis] was attended by a helpful Coast Guard vessel alert to pick up any passengers who plunged overboard and thrust them back…The refugees could even see the shimmering towers of Miami…the battlements of another forbidden city.” The passengers on the S.S. St. Louis had left Germany with joy. Now they were returning there with dread. Passengers pleaded with world leaders to give they asylum so that they could avoid going back to Germany. The Joint Distribution Committee and other agencies did manage to persuade four countries to admit them. They were Belgium, Holland, France, and England. Within a year, however, the Nazis occupied the first three of these countries and most of the passengers eventually perished in concentration camps. Only those in England were saved. Thus, this incident has received the moniker, “The Voyage of the Damned.” For Hitler, the case of the S.S. St. Louis marked a stunning victory. It proved that, in spite of the protestations of the Allied leaders to the contrary, they didn’t want Jews in their countries any more than he wanted them in his. In fact, when a Canadian official was asked how many Jews fleeing from Nazi Europe could be admitted to Canada, he responded: “None is too many.” This eventually became the title of a book, describing Canada’s draconian refugee policies. Unfortunately, our own government was no more hospitable than the rest. To most American Jews, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was a hero. Yet, behind the scenes, he succumbed to the anti-Semitic and nativist pressures of the State Department and placed severe restrictions on the refugee quotas. The S.S. St. Louis incident also underscores the constant need for a strong and secure Israel. Had there been an Israel during the years of the Holocaust, not only would the passengers of the S.S. St. Louis, but thousands, if not millions, of the victims of Treblinka, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and other death camps could have found a place to begin their lives anew. Regardless of our views of some of Israel’s policies, we must acknowledge that it is the only country in the world that will admit an unlimited number of Jews living under duress at all times. One bright spot lightens this dark picture of the S.S. St. Louis. Captain Gustav Schroeder emerged as a hero. He had been on the seas for 37 years before taking over the helm of the S.S. St. Louis. During the voyage, he appointed a passenger committee to maintain calm on the ship when he saw that the situation was desperate. He resisted leaving Cuba and the United States as long as it was humanly possible. On his way back to Europe, he pledged that, if no visas were forthcoming, he would scuttle the ship off the coast of England. He hoped that other countries would pick up and resettle the refugees. The refugees were eventually granted asylum in England, France,

Holland and Belgium. Many of the passengers in continental

Europe later found themselves under Nazi rule as Germany invaded

France and the Netherlands, and eventually were sent to face death in

Nazi concentration camps. |